I’m exhausted.

And not an “I didn’t sleep well last night” exhausted. I mean more of an “I’m at mile 16 of a marathon and my nipples are bleeding” exhausted. At least that’s the emotion that swells within me whenever I hear about another goddamn comic book movie. And make no mistake, there are much more on the way.

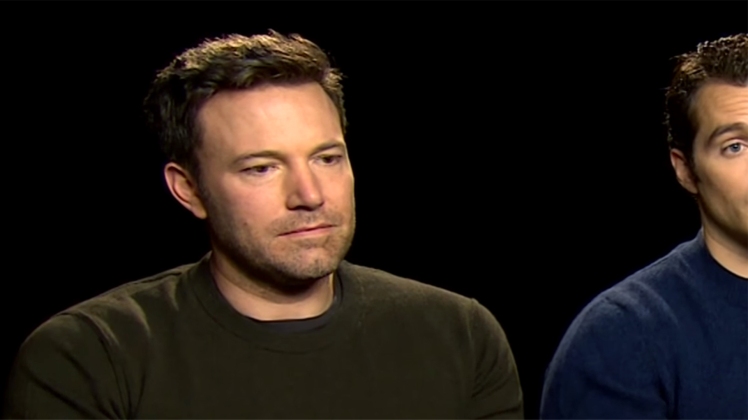

The comic book genre became the quintessential movie genre of this decade through a perfect storm of general fuckery. First came computers. Then TV got really good. Then the internet exploded. Then a recession. And now, we have Sad Affleck.

Let’s go back.

I’M SORRY DAVE, I’M AFRAID I CAN’T DO THAT

Computer Generated Imagery, or CGI, has been used in films since the mid 70s, but it wasn’t until Terminator 2: Judgement Day in 1991 that everyone lost their collective shit. In that film, the T-1000 Cyborg Terminator is made completely from CGI. His metallic structure could morph into any human form, mimicking people perfectly. It was the first mainstream blockbuster to extensively use CGI, and use it in a way that made a previously inconceivable character possible. It opened the door, or should I say box, of CGI in movies. Two years later, CGI would deliver stunning dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. Two years after Jurassic, Toy Story would become the first feature-length CGI animation film. And now, we have Sad Affleck.

Pretty soon, Hollywood and CGI were like two high school kids who became an item. They were holding hands in the hall, making out underneath the bleachers, and experimenting in some great and not-so-great ways. All this was coinciding with a groundswell movement in millions of American homes. TV was getting really, really good.

THE GOLDEN AGE

The Sopranos in 1999 throttled TV into its Golden Age that is now (maybe) coming to a slow ending. This era, led by character-driven shows from the early aughts like The Wire, and The Shield, enabled the coming of the-now modern classics Mad Men and Breaking Bad. Television was now being considered art rather than pulp entertainment as it had been in the pre-Sopranos era. It became much sexier as a medium to writers, because writers were/are treated poorly by the movie studio system. The studios’ interest is not in doing business with writers, but rather their ideas. It’s not uncommon for a writer’s script to be bought, only for them to be swiftly dismissed from a project in favor of a different writer. Up until this Golden Age, films were the only artistic medium screenwriters had. Suddenly, TV was an option, and writers flocked to their new domain. And now, we have Sad Affleck.

COMPETITION

This was then followed by another curveball—the pervasiveness of the internet. Anyone who went to the movies in the mid-2000s will undoubtedly remember this PSA put out by the movie industry. Piracy was just the beginning of the film industry’s troubles when it came to the internet. At the start of this decade, it became clear that streaming platforms were the way of future for content delivery. Netflix and Hulu, and later Amazon, made it possible to have hundreds of thousands of feature-length titles available for the price of one movie ticket. Movie ticket prices, by the way, are at an all-time high. It was the first time since the advent of movie theaters that the industry had ever had a direct competitor, let alone one that didn’t require people to leave their homes. This coincided with the final ingredient in the crockpot of massive twattery, greed.

THE BIG SHORT

The 2008 recession saw many Americans lose their jobs and homes. When the dust settled, American households had lost $11.1 trillion, or 18%, of their wealth. Not only did Americans have less money to spend on leisure, like say, going out to the movies, but the recession, coincided with the crescendo of the Golden Age of TV. Television was practically considered a utility in 2008, right before the rise of the cord cutter movement. Americans had less of a financial incentive than ever to go to the movies. So, the film industry had to figure out a way to make money by delivering something that you couldn’t find on a TV screen. And now, we have Sad Affleck.

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

All these factors above had irreversibly changed the film industry. In a recent episode of the excellent podcast Scriptnotes, hosts John August and Craig Mazin sat down with Crazy-Ex Girlfriend co-creator and showrunner Aline Brosh McKenna and talked about the state of the movie industry from a writer’s perspective. The three of them, who rose in the industry during the 90’s, remarked that many aspects of the business had simply vanished. For instance, the lottery spec script market, wherein a writer would write a script on speculation of selling it, is now essentially gone. As mentioned earlier, studios would buy scripts just to have the rights to an idea, even if the movie was never going to be made. This was the livelihood for many writers, and a way for emerging scribes to break into the business. The same goes for aspiring indie directors, who have seen the mid-budget movie go the way of the DVD. But now, moviegoers can get those fresh ideas on TV or the internet.

Studios figured out that the only experience they can exclusively deliver are massive $200 million blockbusters with action and set pieces that are simply too expensive for other content creators to replicate. It’s high-risk, high-reward. And like any smart business, studios had to find a way to minimize their exposure. Their answer: existing Intellectual Property.

I.P., U.P., WE ALL P

No one wants to spend $200 million. Whether you’re a business or a sovereign government, 200 mill is a lot of scratch. Now what if spending $200 million was the only way you could make money? Wouldn’t you want to do it on something you know people like rather than say, a fresh new idea that might work? Unfortunately, the answer is “of fucking course you would.” And so finally, we arrive at comic books. They make a lot of sense for a few reasons.

First, the backlog of hundreds if not thousands of issues that each comic book franchise possesses provides plenty of material to create a new, modern take on a beloved classic. Second, these massive expanded universes can be packaged and bought in their entirety. Hell, the Walt Disney Company decided it was in their best interest to spend $4.24 BILLION and just buy Marvel outright. And finally, nerdy is the new sexy. The advent of computers, the internet, and everything tech has taken most of what we once considered nerdy and turned it trendy. Comic books were no longer for geeks, they were for sex gods like Ryan Reynolds and Scarlett Johannson (R.I.P. RyLett). But now, we have Sad Affleck.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

There’s nothing inherently wrong or immoral about anything I’ve detailed that led to the rise of comic book movies. The movie business is above all else a business. But given what’s been sacrificed by the industry to get to this point, it’s sad to see the degradation of what was once an exciting genre. There are three indicators of this.

The first is critical reception. The 2008 classic The Dark Knight represented all the potential the burgeoning comic book genre had in the late aughts. It was, as critical aggregator Rotten Tomatoes put it, “dark, complex, and unforgettable.” The Dark Knight at one point held a 99% rating on the site. The same critical acclaim was seen by the other big 2008 release Iron Man, and sister Marvel film The Avengers (2012).

But now it’s 2016, and comic book movies seem like they’re just running through the motions now. The four major comic book movies released so far in 2016 hold in average Rotten Tomatoes rating of 62.25%. This doesn’t even include Warcraft, whose rating is 29%. So the genre has received a collective “meh” from critics all year. Why hasn’t there been a change?

We’re paying them not to.

Box office receipts consistently enable studios to make just okay movies or worse. The worst-reviewed comic book movie of the year so far is Batman v. Superman, which “earned” a 27% rating and spawned the greatest internet meme in history, Sad Affleck. The film has, to date, garnered $872 million from the global box office. Ben’s probably not too torn up about it anymore.

Most of this comes from the overseas market, which represents the most dangerous trend in the film industry. Films are being made with the expectation that they bomb domestically, because they are such hits overseas. This is seen disproportionately in the big budget films, whose explosions and action-packed set pieces are not subject to language or culture barriers. Take Warcraft. That movie cost $160 million to make. It has only made $43 million at the domestic box office, a horrible flop. But overseas, it’s made $368 million. That’s almost 90% of its revenue. All of this points to the final indicator—the genre is tired.

I mentioned being tired at the top of this piece. But the comic book genre has been running its box office marathon for about a decade now, and it’s past tired. It’s fatigued. There’s no greater sign of this than the success of the best comic book film of the year, Deadpool. Deadpool’s whole premise is based around subverting the tropes of the comic book genre, and adding the occasional dick joke. And the tropes were so identifiable, that Deadpool was able to exploit them like clockwork. It went on to make $363 million at the domestic box office. Meanwhile, two other great films have come out in the past month, The Nice Guys and Popstar. Shane Black’s Nice Guys was a critical darling, earning 91% on Rotten Tomatoes. It only just made back its $50 million, making it a financial failure. Popstar fared even worse. The comedy was made for a modest $20 million, and couldn’t even make back half of that ($9.2 mill).

CITIZENS UNITED

Just like in politics, money controls everything. We vote with our dollars. And as long as we continue to vote for the tired comic book genre, we’re going to get it. There are 33 comic book films slated for release in the next five years. I sincerely hope that they’re good. But I’m not optimistic. I’m about as jaded as Sad Affleck.